Last week, the paper A simple proposal for the publication of journal citation distributions appeared online. The first author is Vincent Larivière, a bibliometrician from Université de Montréal, and the last author is Stephen Curry, a biologist from Imperial College and one of the authors of the Metric Tide report published last year by the Higher Education Funding Council for England. Importantly, the paper is co-authored by representatives of a number of prominent journals (Nature, Science, EMBO Journal, and eLife), a publisher (PLOS), and the Royal Society in the UK.

Last week, the paper A simple proposal for the publication of journal citation distributions appeared online. The first author is Vincent Larivière, a bibliometrician from Université de Montréal, and the last author is Stephen Curry, a biologist from Imperial College and one of the authors of the Metric Tide report published last year by the Higher Education Funding Council for England. Importantly, the paper is co-authored by representatives of a number of prominent journals (Nature, Science, EMBO Journal, and eLife), a publisher (PLOS), and the Royal Society in the UK.

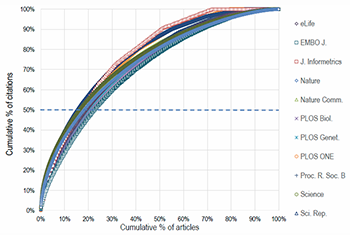

Larivière et al. argue that, when journals report their impact factor (IF), they should also present the underlying distribution of citations over papers. This will draw awareness to the strong skewness of citation distributions and will show that the IF of a journal is determined largely by a small number of highly cited papers.

The idea of complementing IFs with information about the underlying citation distributions is attractive and makes sense to me. I also agree with many of the comments made by Larivière et al. on technical weaknesses of the IF. In this blog post, however, my focus will be on another element of the paper by Larivière et al., namely the distinction made by the authors between the use of IFs at the level of journals and at the level of individual papers.

Journal-level vs. paper-level use of impact factors

Larivière et al. argue that “research assessment needs to focus on papers rather than journals” and that the IF “is an inappropriate indicator for the evaluation of research or researchers”. On the other hand, Larivière et al. also state that they “are not arguing that the journal IF has no value in the comparison of journals”. Hence, according to Larivière et al., IFs can be used for making comparisons between journals, but not for making comparisons between individual papers and their authors.

The question I want to raise in this blog post is what this distinction between the use of IFs at the level of journals and at the level of individual papers actually means. To me it appears difficult to separate these two ways of using IFs. When one uses IFs to compare journals, it seems that usually in one way or another one does so in order to compare papers in the journals. My point is that everyone involved in discussions on the IF needs take a clear and consistent position. In particular, critics of the IF need to accept the full consequences of their criticism. Either they need to fully reject any use of IFs or they need to explain very carefully which uses of IFs should be rejected and which ones are acceptable.

To illustrate my argument, I will provide two examples of the interrelatedness of the use of IFs at the level of journals and at the level of individual papers.

Example 1: Using journals to filter the scientific literature

Suppose a researcher has found two papers that both seem interesting to read, but he has time to read only one of them. The researcher has skimmed both papers, and based on this the two papers seem equally attractive to read. Suppose also that one paper has appeared in a journal that is known to carefully select the work it publishes and to have high quality standards, while the other paper has appeared in a journal that is known to have low standards. Since the researcher doesn’t have any other information that helps to choose which paper to read, the researcher chooses to read the paper in the selective high-quality journal. Based on his knowledge of the two journals, the researcher assumes that the paper in this journal will probably be of more interest than the paper in the other journal.

Approaches like this one to filter the scientific literature seem to be used by almost all researchers. But how do researchers know which journals have strict acceptance criteria and a high level of quality control and which ones adopt lower quality standards? Partly researchers know this from their experience as a reader, author, and referee of journals, and partly they know this because colleagues informally share their experiences as readers, authors, and referees. In addition, researchers may also use quantitative indicators such as the IF to get an impression of a journal’s quality level. This seems to be accepted by Larivière et al., since they accept the use of IFs to make comparisons between journals. However, in our example, the comparison that is made between two journals, either based on personal experience or based on IFs, is used to choose which paper to read. Hence, journal-related information, such as IFs, is used not only to compare journals but also, in an indirect way, to compare papers.

Example 2: Using journals to compare researchers

Suppose a researcher has two colleagues who are each working on their own research project, and suppose each of the two colleagues invites the researcher to join their project. The two projects look equally interesting, but the researcher has limited time available and therefore is able to join only one of the two projects. How to choose which project to join? Without any further information that helps to make a choice, the researcher may decide to look at the past performance of the two colleagues and to choose to collaborate with the colleague who seems to be the more capable researcher.

Determining in an accurate way whether one researcher is performing better than another will often take quite some effort. However, many researchers need to make decisions on whom they want to collaborate with almost on a daily basis, and therefore they need to have a quick way to get at least a rough impression of someone’s capabilities. Researchers may then rely on easily available information, such as the number of papers someone has written during the past years, the journals in which these papers have appeared, and someone’s h-index. Most researchers are probably aware that this information offers only a rough impression of someone’s performance, but for some decisions they may consider it sufficient to rely on such a rough impression.

Suppose the researcher in our example decides to compare his two colleagues by comparing the journals in which they have published. Like in example 1, the researcher will probably take into account his personal experience with the journals, but in addition he may also use quantitative indicators such as IFs. IFs are then used to compare journals and, in an indirect way, to compare researchers.

Taking a clear position

In the above two examples, IFs are used not only to compare journals but also, in an indirect way, to compare individual papers and their authors. Larivière et al. reject the use of IFs to compare papers and their authors, and therefore I expect them to also reject the use of IFs in the above two examples. However, when Larivière et al. state that they “are not arguing that the journal IF has no value in the comparison of journals”, what kind of use of IFs to compare journals do they have in mind? There is a strong interrelatedness of the use of IFs at the level of journals and at the level of individual papers. A simple statement that IFs can be used at the former level but not at the latter one therefore doesn’t seem satisfactory to me.

In discussions on IFs, there are two clear positions that one could defend. On the one hand, one could take the position that in certain cases the use of IFs at the level of journals and at the level of individual papers is acceptable. On the other hand, one could take the position that any use of IFs should be rejected. Although these positions are opposite to each other, they each seem to be internally consistent. Larivière et al. take neither of these positions. They argue that the use of IFs at the level of individual papers should be rejected, while the use of IFs at the level of journals is acceptable. This seems an ambiguous compromise. Given the strong interrelatedness of the use of IFs at the two levels, I doubt the consistency of rejecting the use of IFs at one level and accepting it at the other level.

Conclusion

Discussions on impact factors involve many different types of arguments and therefore have a high level of complexity. To have a fruitful debate on the IF, it is essential that everyone involved takes a position that is clear and internally consistent. Critics of the IF, such as Larivière et al. but also for instance the supporters of the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment , need to accept the full consequences of their criticism. Rejecting the use of IFs at the level of individual papers seems to imply that there also is little room for the use of IFs at the level of journals. In order to be consistent, critics of the IF may even need to further extend their criticism. If one rejects the use of IFs because of the variability in the quality of the papers in a journal, this calls into question whether other types of information on the quality level of journals, such as researchers’ personal experiences with journals, can still be used. Shouldn’t the use of this information be rejected as well? For instance, when deciding which paper to read or which colleague to collaborate with, shouldn’t one completely ignore any information, both from personal experience and from quantitative indicators, on the quality level of the journals in which papers have appeared? This may seem quite an extreme idea, but at least it represents a clear and consistent position, and in fact some have already taken concrete steps to move in this direction.

I would like to thank Sarah de Rijcke, Philippe Mongeon, Cassidy Sugimoto, and Paul Wouters for valuable feedback on a draft version of this blog post.

Below some other publications by CWTS staff members and co-workers on topics closely related to the above blog post are listed:

Blog post by Sarah de Rijcke criticizing too simplistic notions of ‘misuse’ and ‘unintended effects’ in debates on the IF.

Blog post by Philippe Mongeon, Ludo Waltman, and Sarah de Rijcke on journal citation cartels.

Blog post by Paul Wouters on the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment.

Recent research article by Alex Rushforth and Sarah de Rijcke demonstrating how biomedical researchers increasingly use the IF in quite routine knowledge making activities. The article concludes that ‘misuse’ and ‘unintended effects’ are far too simplistic as analytical concepts and offers a new conceptual framework for understanding fundamental effects of the IF on research practices.

Classical research article by Henk Moed and Thed van Leeuwen on inaccuracies in the IF due to technical inconsistencies. A short correspondence on this topic was published in Nature.