Without any doubt, the journal impact factor (IF) is one of the most debated scientometric indicators. Especially the use of the IF for assessing individual articles and their authors is highly controversial. Most scientometricians reject this way of using the IF. They argue that the IF tells something about a journal as a whole and that it is statistically incorrect to extend its interpretation to individual articles in a journal. The well-known San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment, which has received widespread support in the scientific community, also strongly objects against the use of the IF at the level of individual articles. Even Clarivate Analytics, the company that calculates the IF, advices against IF-based assessment of individual articles.

Today we published a paper in the arXiv in which we take a different position. We argue that statistical objections against the use of the IF for assessing individual articles are not convincing, and we therefore conclude that the use of the IF at the level of individual articles is not necessarily wrong, at least not from a statistical point of view.

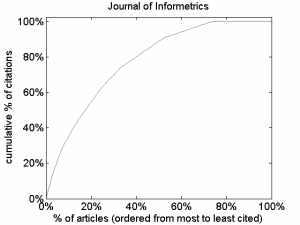

The most common statistical objection against the use of the IF for assessing individual articles is based on the skewness of journal citation distributions. The distribution of citations over the articles published in a journal is typically highly skewed. The figure below for instance illustrates this for Journal of Informetrics. The figure shows that 20% of the articles published in Journal of Informetrics in 2013 and 2014 are responsible for 55% of the citations contributing to the 2015 IF of the journal. Similar results can be obtained for other journals. An extensive analysis of the skewness of journal citation distributions can be found in a paper published last year by Vincent Larivière and colleagues.

Because of the skewness of journal citation distributions, the IF of a journal is not representative of the number of citations received by an individual article in the journal. For this reason, many scientometricians claim that it is statistically incorrect to use the IF at the level of individual articles.

In our paper published today, we argue that this statistical objection against the use of the IF for assessing individual articles is misguided. We agree that the IF is not representative of the number of citations of an individual article, but we do not agree that this necessarily leads to the conclusion that the IF should not be used at the level of individual articles.

The essence of our argument can be summarized as follows. The number of citations of an article can be seen as a proxy of the ‘value’ (e.g., the impact or quality) of the article. However, how accurately citations approximate the value of an article is unclear. Some may consider citations to be a quite accurate indicator of the value of an article, while others may regard citations only as a weak indicator of an article’s value.

When citations are seen as a relatively accurate indicator of the value of an article, the skewness of journal citation distributions implies that the distribution of the values of the articles published in a journal must be highly skewed as well. In this situation, we agree that it is statistically incorrect to use the IF for assessing individual articles.

However, things are different when citations are regarded as a relatively inaccurate indicator of the value of an article. It is then possible that the articles published in a journal all have a more or less similar value. This might for instance be due to the peer review system of a journal, which may ensure that articles whose value is below a certain threshold are not published in the journal. When citations are a relatively inaccurate indicator of the value of an article, some articles in a journal may receive many more citations than others, even though the articles are all of more or less similar value. This may then cause the citation distribution of a journal to be highly skewed, despite the fact that the journal is relatively homogeneous in terms of the values of its articles. In this scenario, assessing individual articles based on citations may be questionable and assessment based on the IF of the journal in which an article has appeared may actually be more accurate.

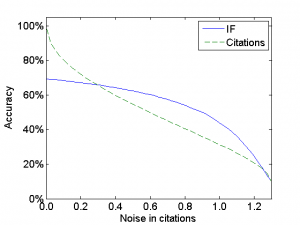

In our paper, the above argument is elaborated in much more detail. We present an extensive conceptual discussion, but we also report computer simulations to support our argument. The figure below shows the outcome of one of the simulations that we have performed. The horizontal axis indicates how ‘noisy’ citations are as a proxy of the value of an article. The higher the value along this axis, the more citations are affected by noise and the more difficult it is to obtain a good proxy of the value of an article. The vertical axis shows the accuracy of both citations and the IF as indicators of the value of an article. As can be expected, the more citations are affected by noise, the lower the accuracy of both citations and the IF. When there is little or no noise, citations and the IF both have a high accuracy, but the IF is less accurate than citations. Importantly, when the amount of noise increases, the accuracy of citations decreases faster than the accuracy of the IF, and therefore the IF becomes more accurate than citations. For large amounts of noise, citations and the IF both become highly inaccurate.

Our conclusion is that statistical considerations do not convincingly support the rejection of the use of the IF for assessing individual articles and their authors. Whether the use of the IF at the level of individual articles should be rejected and whether article-level citation statistics should be preferred over the IF depends on how accurately citations can be considered to represent the value of an article. Empirical follow-up research is needed to shed more light on this. From a statistical point of view, it is not necessarily wrong to use the IF for assessing individual articles. Scientometricians need to reconsider their opinion on this issue. On the other hand, we recognize that there may be important non-statistical reasons to argue against the use of the IF in the evaluation of scientific research. The IF plays a pervasive role in today’s science system, and this may have all kinds of undesirable consequences. The debate on the IF is highly important and should continue, but it should not be based on misplaced statistical arguments.

Earlier blog posts on the IF and related topics:

- Q&A on Elsevier’s CiteScore metric

- Journal self-citations are increasingly biased toward impact factor years

- Let’s move beyond too simplistic notions of ‘misuse’ and ‘unintended effects’ in debates on the JIF

- The importance of taking a clear position in the impact factor debate

-

What do we know about journal citation cartels? A call for information